Reflections on the Great NCAC-USAEE 2019 Annual Conference

Thanks to everyone who participated in the annual NCAC conference at George Washington University on Wednesday, April 24. The members made it a great success. More than one hundred people attended. Special thanks go to conference chair and NCAC VP David Givens, and to NCAC President Michael Ratner. David managed the entire event and Michael secured our keynote speaker, General David Petraeus. Photos of the event can be found here.

Sign Up for May 8 Lunch – Topic is U.S. LNG and European Energy Security

The speaker is Keith Martin, Chief Commercial Officer, Uniper

Uniper is an international energy company active in more than 40 countries that owns and manages power plants throughout Europe and Russia. The company also engages in commodity trading in natural gas, liquefied natural gas, coal, emission certificates, and freight. Uniper employs roughly 12,000 people, and boasted €78 billion in sales in 2018. It is active in the export of US coal and LNG and is planning an LNG floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) at its site in Wilhelmshaven, Germany.

Energy Hedging Class - May 2-3, 2019

By Elaine Levin

NCAC members have shown a lively interest in Futures markets. After all, Futures markets are really different from the traditional physical markets that most of us learned about in introductory economics classes. Futures markets offer a unique way to control costs and budgets for energy producers, governments and private companies for whom energy is an important input.

Powerhouse’s principals have frequently offered training to NCAC members in Futures as they relate to energy markets. Attendees have been overwhelmingly satisfied with the experience.

Powerhouse will be offering a new course on Practical Fuel Hedging on May 2nd and 3rd at the Georgetown Inn here in Washington. You’ll learn how to use Futures and Options on Futures in two days of intense and immensely satisfying training focused on practical applications of the Futures contract suite.

The course will cover:

- Identifying price volatility’s impact on profits

- The vocabulary of hedging

- How Futures and Options on Futures differ

- Explaining basis

- Using seasonality

- Creating hedge strategies

This is a course you won’t want to miss. To register or get more information:

Visit http://powerhousesp.com/pfh/

Email registrar@powerhousetl.com or call (202) 333-5380

Saudi Aramco Inaugural Offering

By Rita Beale

In April, Saudi Arabian Oil Company (“Saudi Aramco”) débuted in the international capital markets pricing $12 billion of corporate debt through five tranches of 3- to 30-year dollar-denominated senior unsecured notes carrying coupons of 2.75% to 4.375% to be traded on the London Stock Exchange’s Regulated Market.

The offering was notable in several ways – strong investor confidence of a new emerging market security (investor orders of $85-100 billion), revelation of the world’s most profitable company ($111 billion of net income in 2018 with the sum of Apple plus Google plus Exxon Mobil), normalization of Saudi Aramco’s financial reporting and business practices toward international standards (underway since 2017), and standing as a milestone in Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s plan to diversify the Saudi economy.

Bond issuance appears to be a shrewd way to test acceptance by international investors, following the delay of an Initial Public Offering, now planned for 2021. Debt carries advantages versus equities, given their even tighter transparency requirements, potential investor demands for greater control of the company, and potentially higher cost, particularly if dividends were competitive with other international oil companies.

The notes have investment grade credit ratings of A1/A+, slightly below the levels of Exxon, Shell and Chevron and at similar levels as the sovereign debt of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The risks in the Prospectus underscored the Kingdom’s ownership of the resources, its authority over the 40-year operating leases and fiscal regimes, as well as the Kingdom’s reliance on Shari’ah principles. Fund flow from operations at $26 per barrel in 2018 was noted to be $5 to $12 per barrel lower than Total SA and Shell respectively, largely due to the heavy income taxes, royalties, and dividends paid to the Kingdom.

Financial information in the Prospectus also generated various analyst viewpoints about potential equity price levels should a Saudi Aramco equity issuance ever come to fruition. The size of the debt offering suggests ability to return to global investors for future issuances, given the perception of low overall debt levels.

Rita Beale is Managing Partner of Energy Unlimited LLC. Ms. Beale’s first career was in financial services at marquee New York broker-dealers as a research commodity analyst, advising institutional clients on global markets and futures/options hedging and trading strategies. The author relied on information from reputable news agencies and does not have ownership of any Aramco securities.

Arrival of the Hydrogen Economy

by Henry P. Aszklar, Jr.

In his 2003 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush announced the arrival of the hydrogen economy that would unshackle the U.S. economy from fossil fuels and provide a clean, carbon-free energy environment. And then we waited, and waited, and waited. Today hydrogen is starting to fuel an energy transformation in California, with over 6,000 fuel cell electric vehicles on the road and 39 retail hydrogen refueling stations. California is leading the charge toward the goals set out by the 2005 U.S. Energy Policy Act to enable production, delivery, and acceptance by consumers of model year 2020 hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles. Unfortunately, the rest of the U.S. lags far behind, but as the fifth largest economy in the world, California has the engine to pull the rest of the U.S. into the hydrogen economy.

So why should we be cheering on California? A 2017 report by the Hydrogen Council, co-authored by global consulting firm McKinsey and Company, emphatically states that the technology is proven, and what remains to be done is the scaling up of existing technologies, combined with starting the virtuous cycle of deploying hydrogen technologies across the energy sector with the economic benefits of manufacturing fuel cell electric vehicles - 400 million cars, 15 to 20 million trucks and 5 million buses by 2050. And where will these cars, trucks and buses be manufactured? Hopefully here in the U.S. But China and other countries are giving the U.S. a run for the money. It would be tragic if the manufacturing base for the hydrogen economy ends up going the same way as the solar industry – to China.

Toyota and Hyundai recently broke ground on manufacturing facilities to support the production of 30,000 to 40,000 fuel cell electric vehicles by 2020. Toyota currently sells fuel cell electric vehicles in eleven countries and expects to sell 10,000 per year in Japan by 2020. Today there are 50 hydrogen refueling stations in Germany, and more than 100 in Japan. Toyota has begun selling its fuel cell electric buses and expects to have 100 in operation in Tokyo in time for the 2020 Olympics. A 2018 Global Executive Survey of leading automotive companies by KMPG indicated that most believe fuel cell electric vehicles will serve as the key breakthrough to fully enable electric mobility.

A 2017 report by the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory on the current status of fuel cell electric powered buses assessed the technology readiness level range from 7 to 8, with 9 reflecting a mature technology, such as diesel. The report noted that fuel cell stacks are reliable and robust, with most of the problems instead associated with the balance of plant. The report further notes that durability of the fuel cell stack in older buses has surpassed the ultimate target of 25,000 hours without repair or replacement of the fuel cell.

The hydrogen economy has landed on the shores of California. Let’s hope that the U.S. has the foresight and ability to develop the associated manufacturing base within our borders and not let hydrogen technology go the way of solar photovoltaics.

Henry Aszklar is a senior energy advisor working with renewable energy companies, private equity funds, and multinational technology and service providers. He is a member of the U.S. Department of Energy Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technical Advisory Committee, as well as a board advisor to a community solar company.

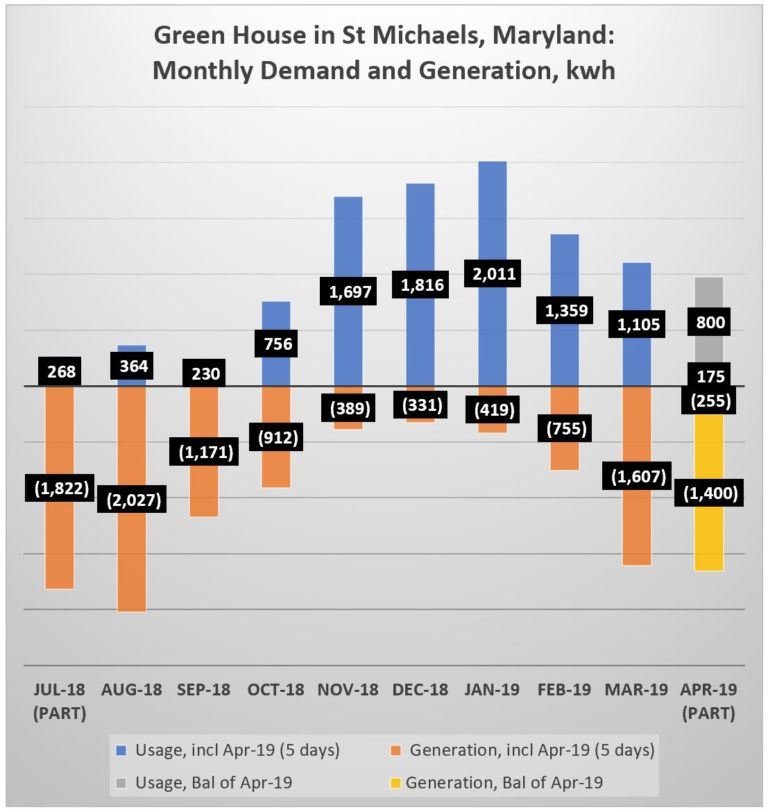

Green House in St Michaels – Mid-April 2019 Update

By Ben Schlesinger

http://bsaenergy.com/wordpress1/

Now nine months into our carbon net-neutral experiment, the house is still amazing. It’s already generated about as much electricity as it’s consumed, and the remaining three months (mid-April through mid-July) typically have easy weather and sunshine. The info from Choptank Electric Cooperative’s website tells the story so far

Now nine months into our carbon net-neutral experiment, the house is still amazing. It’s already generated about as much electricity as it’s consumed, and the remaining three months (mid-April through mid-July) typically have easy weather and sunshine. The info from Choptank Electric Cooperative’s website tells the story so far

– Starting from July 12, 2018, when our 50 solar PV panels went live, our electricity generation in the summer and early fall far outstripped power demand in the house, which was mostly for cooling and construction equipment. Having a highly-insulated shell helped too.

– Then, this pattern reversed during peak winter months, when the low sun angle and even some snow cover made solar less effective. Our 8-well geothermal energy system was seasonally less productive as well, but the house’s 45 SEER ground-source heat pumps still used much less energy than conventional heat pumps while also providing hot water.

– So far in late winter and spring 2019, our solar PV ‘power plant’ is once again out- producing household demand, on average.

But even though the house is indeed net-negative in terms of energy use (produces more than it uses), we wonder if this means we’re also meeting our goal of carbon net-neutrality? I suspect it does mean that, but we’ll need to use quarter-hour PJM fuel use data to prove the point, i.e., see exactly what fuels we’re displacing. On the positive side, we can widen the circle and include carbon avoided by charging electric cars with solar power versus using gasoline cars. We’ll also try managing our 3 Tesla batteries this spring to minimize carbon production, as discussed in last month’s blog – up to now, we’ve held these for emergency power supply in the winter. On the negative side, there’s our prodigious lawn that needs to get cut weekly with conventional smelly equipment – we’re considering an electric mower. We’ve also got propane distributed through the house to gas fireplaces and the cooktop, but these are basically cosmetic uses, a few gallons per month.

Bottom line is we’ve got a zero-energy house, producing more than it consumes over an annual cycle. We’re still gathering info to prove the same point for carbon, and we’ll also be able to assess the basic economics of this experiment, including years to pay-back and internal rate of return of our incremental investment. As always, the devil is in the details! More to follow.

Ben Schlesinger, founding president of Benjamin Schlesinger and Associates (BSA), is a leading independent energy consultant. As the principal independent gas advisor to NYMEX, Dr. Schlesinger helped write the highly successful NYMEX gas futures contract, prepared the analytic justification for Henry Hub before the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), and helped design gas swap futures contracts throughout the US and Canada.

How local leaders can make their communities more EV-friendly

By Josh Cohen

While much of the electric vehicle (EV) policy conversation focuses on state legislatures and public utility commissions, local governments have an important role to play too. Cities and counties are where the rubber meets the road, so to speak, and local policies can go a long way towards increasing EV adoption.

In last November’s midterm elections, thousands of new mayors, county executives, councilmembers and commissioners were elected to local office. As these local leaders begin serving their terms, here are eight actionable, concrete steps they can take to accelerate EV adoption in their jurisdiction.

Lead by example

Fleets: Establish targets to replace government fleet vehicles with EVs, starting with widely available light-duty passenger EVs and electric transit buses. Set future targets for medium- and heavy-duty EVs as they become more widely commercially available.

Existing facilities: Install charging stations at government-owned facilities such as public parking garages, office buildings, libraries, schools, parks and other destinations.

Capital projects: Require new government capital projects to include “EV ready” spaces with pre-installed conduit, 208/240-volt 30-amp wiring and two pole 40-amp breakers. Why? It’s measurably less expensive to wire parking spaces during construction than to retrofit them afterwards. Then, once funding becomes available to purchase the charging stations, little or no additional expense will be needed.

Grants: Pursue grant opportunities that offer significant subsidies or rebates for EVs and EV charging stations. Local governments are tax-exempt and don’t benefit from tax credits, but free money always helps. For instance, states and tribal nations can allocate much of their $2.9-billion share of the Volkswagen “dieselgate” settlement towards grants for EV charging stations, electric school and transit buses and freight trucks. These grants are low-hanging fruit for local governments to pursue.

Legislate

New construction: Enact ordinances and building codes that require EV-ready spaces in new construction. Different jurisdictions take different approaches, but generally they require single-family homes and some portion of parking spaces at multi-family and commercial properties to be EV-ready. Examples are found across the country and include Atlanta, Denver, New York City, San Francisco, and Maryland’s Howard County.

Tax credits: Enact a property tax credit so property owners can receive a one-time credit for the costs of charging station purchase and installation. Tax credits can be capped at different dollar amounts depending on the station type (e.g. Level 2 or DC Fast Charge) and should be broad enough to apply to both purchase and installation costs.

Driver incentives:Offer incentives for EV drivers, for instance by waiving the entry fee at county parks or by allowing EVs to receive an hour of free parking in municipal lots. Driver incentives don’t have to cost the government a lot of money. Small but noticeable incentives can have an outsized impact in making a community more EV-friendly.

Collaborate

Regional planning:Establish a plan for priority charging routes and destinations that is informed by local input and implemented in coordination with neighboring jurisdictions. Local government plans should align where possible with federal and regional routes such as Alternative Fuel Vehicle Corridors and should complement other investments by state agencies, Electrify America and other entities.

By putting these recommendations into action, local leaders will do more than make their communities more EV-friendly; they will also be more competitive when it comes to attracting jobs and businesses for which EV charging is no longer an amenity but an expectation.

Josh Cohen is Director of Policy and Utility Programs at SemaConnect, a leading national provider of smart, networked EV charging solutions. Josh served 12 years in local elected positions, including a term as mayor of Annapolis, Maryland. He can be reached at josh.cohen@semaconnect.com. This article originally appeared in the March/April 2019 issue of Charged EVs magazine.

Should Electric Vehicle Drivers Pay a Mileage Tax?

EV drivers don’t pay the gasoline tax, so pay less for roads.

By Lucas Davis and James Sallee

From the energyathass blog at the Haas School of Business, University of California Berkeley-Blog: Should Electric Vehicle Drivers Pay a Mileage Tax?

Every time we buy a gallon of gasoline, we help pay for roads. 18 cents go to the U.S. Highway Trust Fund. Here in California, 30 cents go to the state’s Road Maintenance and Rehabilitation Program.

EV drivers don’t pay the gasoline tax, so they pay less for roads. Several states are considering imposing a mileage tax on electric vehicle drivers to make up for the lost revenue.

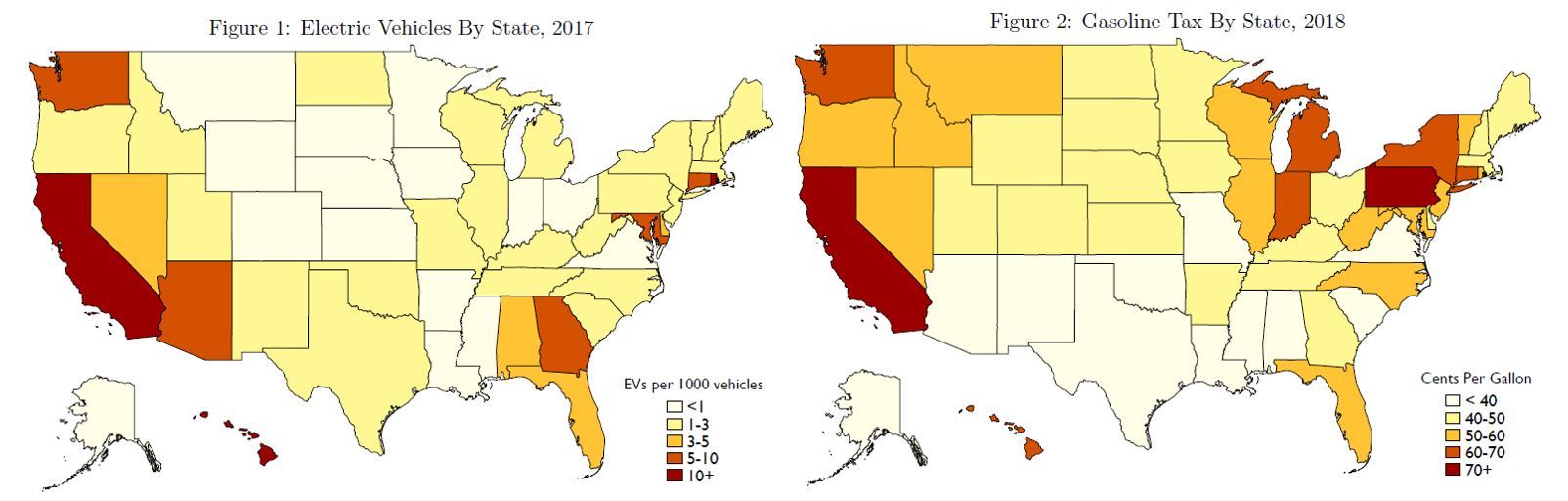

How much lost revenue are we talking about? And does this policy response make sense? In a new Energy Institute working paper, we ask, “Should Electric Vehicle Drivers Pay a Mileage Tax?”

Growing Hole in Road Budgets

According to our calculations, EVs have reduced U.S. gasoline tax revenues by $250 million annually. Of this, 30% ($75 million) is foregone federal tax, while the other 70% ($175 million) is foregone state and local tax.

For this we assumed that EV drivers would have otherwise been driving 15,000 miles per year in a 28.9 mpg gasoline-powered vehicle. These assumptions follow recent economic research (here and here), though we also report calculations based on, for example, fewer miles driven.

We also take into account the highly uneven pattern of EVs across states. As these maps illustrate, there tend to be more EVs in states with higher-than-average gasoline taxes (correlation 0.46). This correlation increases the gasoline tax revenue impacts by about 20%.

Gasoline taxes include all federal and state taxes including components not explicitly targeted at roads.

This $250 million annually in missing revenue represents less than 1% of total gasoline tax revenue. After all, EVs are less than 1% of the U.S. vehicle stock, so it makes sense the aggregate impact is so far pretty modest. Still, the impact per EV is substantial — $318 annually according to our estimates.

In addition, the missing revenue is highly concentrated in a handful of states. We calculate that for California alone the missing revenue is $90 million annually. California aims to have 1.5 million EVs on the road by 2025, and 5 million EVs on the roads by 2030, 10 times the number today. So, this trickle could soon turn into a flood.

The missing revenue is also highly regressive. We find that two-thirds of the missing revenue comes from households with $100,000+ in annual income. This reflects, as you might have guessed, that EV drivers continue to be disproportionately very high income.

But Wait a Minute

Right about now all the EV drivers are breathing heavily. “Yeah sure, we use the roads, but we create environmental benefits too!”

Yes, according to the latest analysis from Holland, Mansur, Muller, and Yates, EVs do tend to be less damaging than gasoline vehicles. It depends on where you drive, but the U.S. electric sector continues to get cleaner, which reduces the environmental damages from plugging in an EV.

That said, the environmental damages from EVs are not zero. Also, don’t forget, EVs cause traffic congestion and accidents, just like any vehicle. Ian Parry and other economists have argued that these “mileage externalities” are actually larger than the environmental externalities from driving.

Growing Interest in Mileage Taxes

With this as a backdrop, several states are now considering implementing a mileage tax. California, Washington, and Illinois have all conducted mileage tax pilots, and Oregon passed legislation allowing 5,000 voluntary motorists to pay a mileage tax of 1.7 cents per mile, in lieu of gasoline taxes.

A mileage tax would likely be more efficient than a gasoline tax for targeting traffic congestion and other mileage externalities. After all, vehicles create traffic congestion regardless of whether they get 10mpg, 50mpg, or 100mpg. Moreover, a mileage tax would help plug the hole in road budgets.

Mileage taxes are not a panacea, however. For example, traffic congestion depends on where and when you drive. Some people drive on crowded freeways at rush hour, while others drive on uncongested roads at 2am. As Severin Borenstein points out, what you would really like to do is tax all externalities using time-varying, location-varying dynamic prices.

Key Tradeoff

So suppose we transition to a mileage tax. Let’s assume, moreover, that at least for the moment, the “tax all externalities” dynamically is off the table. In the paper we develop a model of driving under these circumstances and ask what level of mileage tax makes sense for EVs. This exercise highlights a key tradeoff.

On the one hand, driving an EV does generate externalities, which leads you to want to impose a mileage tax on EVs. On the other hand, gasoline-powered vehicles generate externalities too, and there has been a tendency to underprice these externalities. For example, many economists believe that gasoline in the United States is significantly underpriced.

If the externalities from gasoline-powered vehicles are sufficiently underpriced, then you don’t want to impose a mileage tax on EVs. To the contrary, you may actually want to subsidize drivers to use EVs, just so they won’t drive in gasoline-powered vehicles. One possibility would be to subsidize EV purchases, as is currently done, for example, with state and federal EV credits, while simultaneously imposing a mileage tax on EVs.

But again, none of this is as good as the “tax all externalities” approach. Perhaps the biggest benefit of moving to a mileage tax would be that, in the longer-run, it becomes easier to implement more dynamic pricing. With the gasoline tax this is impossible, but it would be relatively easy, for example, to move from a simple mileage tax to one that varies by location and hour-of-day.

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. James M. Sallee is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Berkeley.